18 Dec To Make a Marchpane (Marzipan)

Then Serve It Forth…

By Lady Rosemary Willowwood de Ste. Anne

“Christmas is a-coming and the geese are getting fat…” I explained last month one of the things you could do with a goose – now let’s move on to the fancier trimmings. Yule feasts, especially in the royal households, have been a time to pile on the gilding and decorations to fancy up the feast. Which, of course, brings us to the subject of “subtleties”. Subtleties, those jaw-dropping decorations designed to evoke tributes, awe, and wonder in the people who demolished them, were frequently constructed of marzipan, called “marchpane” in the medieval cookery books.

To make a Marchpane

from Delightes for Ladies, . . . with Beauties. Banquets. Perfumes and Waters

By Sir Hugh Plat, publ. London, 1609

Take two pounds of Almonds being blanched and dryed in a sieue over the fire: beat them in a stone mortar; and when they bee small, mix with them two pounds of sugar being finely beaten, adding 2 or 3 spoonfuls of Rose-water, and that will keeps (sic) your Almonds from oyling. When your paste is beaten fine, drive it thin with a rowling pin, and so lay it on a bottom of wafers: then raise up a little edge on one side, and so bake it: then yce it with Rose-water and sugar: then put it into the ouen again; and when you see your yce is risen vp & dry, then take it out of the ouen & garnish it with pretty conceits, as birds and beasts, being cast out of standing moulds. Stick long comfits vpright in it; cast biskits and carrowaies in it,: gild it before you serve it: you may also print off this Marchpane paste in your molds for banquetting dishes: and of this paste out comfitmakers at this day make their letters, knots, Arms, Escocheons, beasts, birds, and other fancies.

TRANSLATION (Plat’s recipes actually take little translation if one remembers a few rules of interpretation: If you see a word you don’t recognize, substitute “u” for “v”, “v” for “u”, “i” for “y”, and when all else fails, sound it out. There was no standardization in spelling conventions in those days.) Take two pounds of almonds being blanched (see glossary) and dried in a sieve over the fire: beat them in a stone mortar; and when they be (ground) small, mix with them two pounds of sugar being finely beaten, adding 2 or 3 spoonfuls of rosewater, and that will keep your almonds from (becoming) oily. When your paste is beaten fine, drive it thin with a rolling pin, and so lay it on a bottom of wafers: then raise up a little edge on one side, and so bake it: then ice it with rosewater and sugar: then put it into the oven again; and when you see your icing is risen up & dry, then take it out of the oven & garnish it with pretty conceits, as birds and beasts, being cast out of standing moulds. Stick long comfits (see glossary) upright in it; cast cookies and caraway seeds in it,: gild it (see glossary) before you serve it: you may also print off this Marchpane paste in your molds for banqueting dishes: and of this paste out comfit-makers at this day make their letters, knots, Arms, Escutcheons, beasts, birds, and other fancies.

REALIZATION: The basic proportions for this recipe haven’t changed in over four hundred years. Both the Fannie Farmer cookbook of 1936 and Joy of Cooking of 1979 use essentially the same basic proportions, if a somewhat less laborious technique. Two pounds of blanched almonds is a workable quantity, although if you are smoothing it in a real mortar and pestle, you will be limited by the size of your mortar. Just keep the proportion of almonds and sugar equal by weight. Grind the almonds fairly fine in a meat chopper, blender, or food processor. If using the latter two, be careful that you stop before you reach the “nut-butter” stage; add two to three T. of rosewater to prevent the “oiling” of the nuts. Add the sugar, and blend until smooth, adding additional rosewater by teaspoon until you have a smooth paste. The paste will be easier to work if you allow it to season in an airtight container for a day or two. To work the paste, cover your board in powdered sugar and knead until smooth. This is also the time to knead in color. The medievals had all sorts of ways to create color in marzipan, but often at the price of taste; I’ll sacrifice accuracy with vegetable food coloring to avoid the taste of parsley in MY green almond paste!

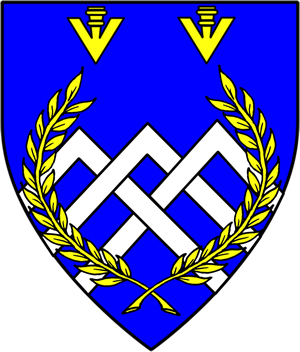

Now that you have marzipan, let your imagination run wild! Remember all the fun you had in kindergarten with Play-Dough? You can do almost the same with this wonderful stuff. Roll with a rolling pin, use cookie cutters, sculpt, carve, anything you like. Make birds, and flowers, and cats and dogs, and dishes, and kings and queens, create your dream castle, or coat of arms, or anything else your imagination can devise. Dry your creations in a warm oven, not over 140 degrees, for a couple of hours, or better, two hours at 140, turn off the oven and leave overnight. Once dry, you can glaze with an icing of sugar and rosewater. If you wish to paint the figures, use powdered sugar mixed to a thick paste with rosewater and colored with food coloring, applied with a paint-brush. If you want a clear glaze, dissolve two pounds of granulated sugar in two cups of water, cook without stirring until it spins a thread (230 degrees on a candy thermometer), cool the glaze completely, then paint on and dry again.

Some general construction tips: tall structures may require some support while drying. Cardboard forms can be sued for support and carefully removed later. Or plan flat construction, and use royal icing to assemble in the same way you would a gingerbread house. There will be many magazines on the newsstands this month to provide ideas.

GLOSSARY:

Marchpane: Almond paste. Also call marzipan, both in its molded and unmolded form..

Blanched almonds: Almonds with the brown outer skin removed. To blanch almonds, pour a generous amount of boiling water over shelled nuts. Let stand 1-2 minutes, drain. Handled hot, the skins should slip off to a gentle pressure. As they cool, you may need to repeat the process, but do not soak the nuts too long.

Comfits: Candied seeds, some as small as a lightly coated caraway or anise seed, some approaching the size of a small jaw-breaker, depending on your taste. Often flavored with orange-, rose-, violet-, or lavender-flower waters

Gilding: Foods were frequently coated with real gold and silver leaf for show, and the gilding was eaten right along with the food gilded. This tradition is maintained in the Middle East and India even today, and edible gold leaf can be found with a little searching. However, DON’T BE TEMPTED TO TRY THIS WITH ARTIST’S LEAF. I haven’t asked an authority, but I’m sure it is not approved for human consumption.